In Finding the Family Farm, I talked about my surprising discovery that my great-grandfather George Lindley Coulson, the Yorkshire coal miner, had a brief stint as a homesteader in the Black Hills of Wyoming in the opening years of the 20th century. Surprising, because the family lore doesn’t mention it, and his background was about as far from farming as you could get. I am considering the possibility that his foray into homesteading was a fraudulent scam, and that his employer at the time, the Cambria Coal Company, was behind it.

A decade later, after putting his family through a grueling migration to Saskatchewan that saw the death of his wife and one of their children, he became a farmer again in 1917 at the age of 53, when the vigor of youth was long past.

What kind of a farmer was he? “Lazy,” said George Arthur Coulson, George Lindley’s youngest son, my grandfather. George Arthur told a story about his time on that last farm in an attempt to explain why he walked away from his father and never looked back.

It was 1918 and winter was coming on. George Lindley and his second wife Mary found the farmhouse they had moved into a year earlier too cold and drafty, and so they decided to go down to the big city to stay in a cozy hotel for the winter, leaving young George Arthur in charge of the farm. There wasn’t much to do, just feed the livestock and go to school. So they all rode together to Lac La Biche, then the northern terminus of the brand-new Alberta and Great Waterways Railway. George Arthur saw his folks off for their winter holiday in balmy Edmonton, and then he took the horses back home to the farm which lay 20 miles to the west.

George Lindley could afford to spend the whole winter in a hotel in the big city because, for the first time in his life, he was rich… though not through any fault of his own. Three years earlier in Havre, Montana, he had met and married Mary Griffin, the wealthy widow of the successful rancher and local character “Bear Paw” Jack Griffin. She was loaded.

George Arthur, at 13, was the last of George Lindley’s six surviving children still under his father’s tender care. George Arthur did not like the arrangement. He especially did not like his new step-mother. He was still grieving over the loss of his real mother, Lucy Scarlet, who died of tuberculosis and exhaustion when he was only 7. My grandfather remembered the name of the place where the farm was located with great disdain: Plamondonville. He was an outsider from a foreign culture, the other kids picked on him, and he hated it there.

Plamondonville actually has a pretty interesting history. It was settled by families of French Canadian expatriates who had migrated from Quebec to Michigan after the U.S. Civil War. Prior to 1907 one enterprising resident, Isidore Plamondon, ventured north into the newly-created Canadian province of Alberta, and came back to proclaim it a promised land for farming. They found a spot to settle in northern Alberta west of Lac La Biche, and families went north from Michigan in droves over the next few years, making Plamondonville (today, simply called Plamondon) into a vibrant French-speaking, Roman Catholic community.

How my great-grandfather, an English Anglican Protestant, found his way up there, is one of those enduring mysteries I have yet to unravel.

Anyway, back to my grandfather’s story. The Spanish Flu came to Plamondonville that winter, so bad it shut down the school. George Arthur caught it, and he lay in bed, delirious, for days, completely alone, not knowing if he would live or die. He finally recovered, and was able to drag himself out to the barn to open the doors. The horses were mad with hunger by then, and they almost trampled him on their way to the haystack.

George Lindley and Mary returned from their happy holiday in Edmonton in the spring, and George Arthur was resentful of how they had, unknowingly, abandoned him to his doom while they were having a high old time. But soon there was another crisis to contend with: George Arthur got into trouble. He claimed that he had been bullied by some boys and had to fight back. But in fact, according to his own telling, he had been caught riding down some French boys on his pony and whipping them with his riding crop. Is this the action of a boy defending himself from bullies? I am inclined to think that Grandpa was the bully here. Whatever the truth of the matter, he told the story as if he really believed he were the injured party.

As you can imagine, his step-mother Mary got a visit from the parish priest, tout-suite. This must have caused Mary considerable embarrassment. She had raised eleven children back in Montana and had managed her first husband’s ranch for 20 years, and she knew a thing or two about child-rearing, but apparently she didn’t know what to do with George Arthur’s defiance. He was too strong to be whipped, and his father was too chicken to intervene in this long-simmering dispute, so they were at a stalemate. Finally he asked her,

“What’s it worth to you to get rid of me?”

Mary answered,

“Look under the cookie jar tomorrow morning.”

The next morning George Arthur got up early and looked, and found twenty dollars under the cookie jar. And so he saddled his pony and rode in to Lac La Biche, sold the saddle, and pocketed the money. Then he parked the pony at the livery stable (because the pony did, after all, belong to his dad), bought a train ticket, and caught the A&GW to Edmonton.

At that point Grandpa’s story falls silent, but I know he wound up living with his big sister Mary and her husband, who had a farm and ran a hotel in Govenlock, Saskatchewan. His sister’s husband, John Lindner, came from a large, respected family of ranchers in the Cypress Hills, and they took George Arthur in, financed his further schooling, and helped him get started on his long railroad career. He never saw his step-mother again, and only saw his father one more time, briefly, twenty years later. That story will be the subject of a future blog post.

This blog post, believe it or not, is not about George Arthur; it’s about the farm in Plamondonville, and how I tracked down its location.

First, let’s lay out the evidence I started with.

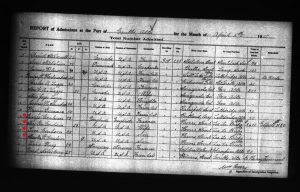

I know that George Lindley brought his family to Plamondon no earlier than 1917, because I have the record of their border crossing at the port of Coutts, Alberta, on April 5, 1917. Notice that George L. is carrying $3,600 in cash– quite a lot of money. I am pretty sure that is Mary’s money from the sale of her late husband’s estate a few years earlier.

Tom, George Lindley’s eldest son, came with them on this trip, but he does not figure in the story because he went off and started working on other farms in the region.

Grandpa’s reference to the Flu pandemic anchors the story in either the winter of 1918-19 or 1919-20, because influenza ravaged Plamondonville both winters. By April of 1921 (when the Canadian Census was taken), he was living in Govenlock, Saskatchewan with his sister.

George Coulson is living with John and Mary Lindner and their daughter Lucille in 1921. George is listed as “bro in law” to John.

So George Arthur left Plamondonville and never came back, but George Lindley and Mary stayed on. How long did they continue to live there? Well, they are still there in April 1921, as they appear in the census that year:

The Coulson family in the 1921 Census. The identity of the 10-year-old Cree boy, William Swain, who is living with them as an “adopted” son, will be the subject of a future blog post.

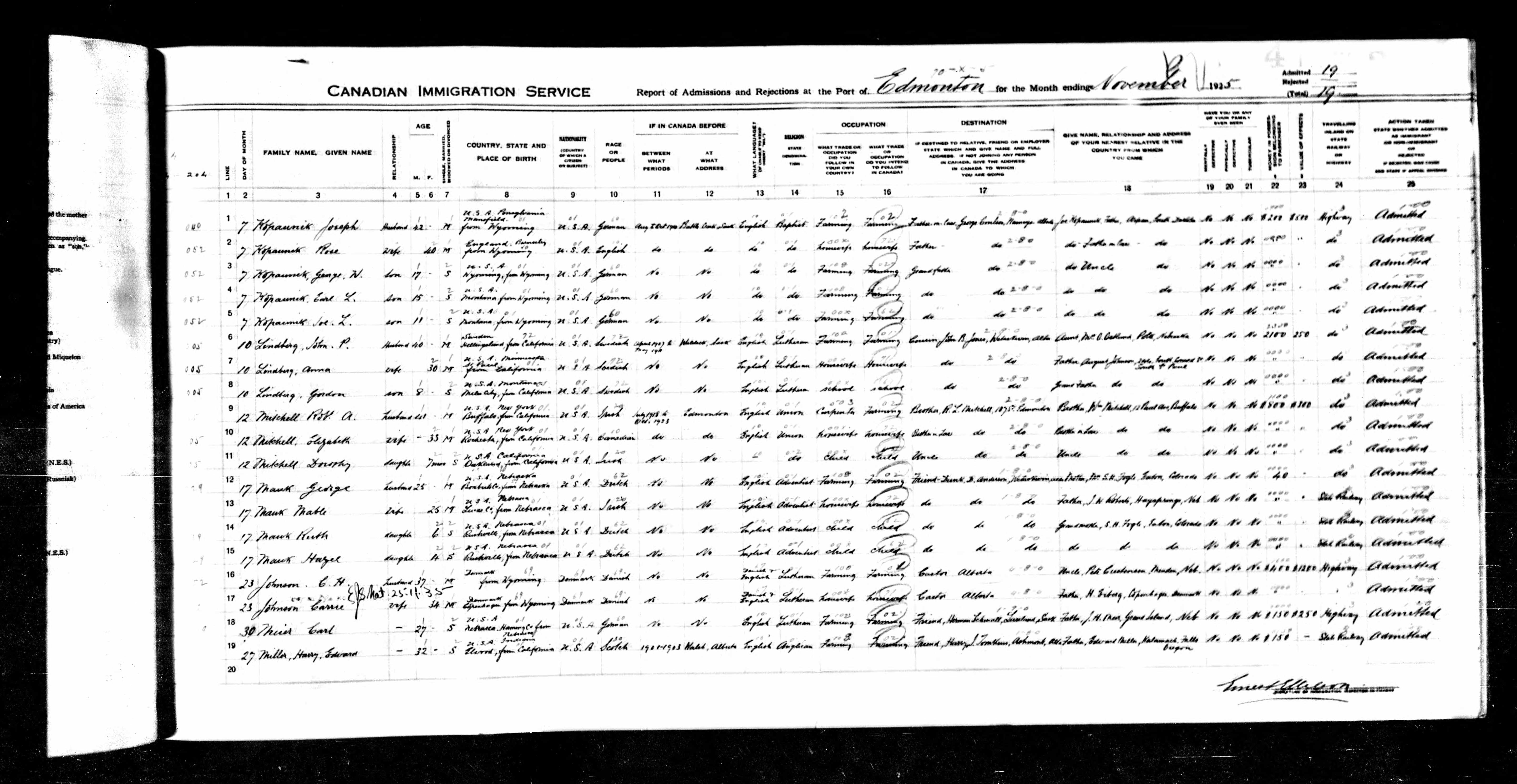

At some point George Lindley and Mary must have left Plamondonville, because I know they died in Edmonton (in 1940 and 1938, respectively), but when did they leave? The earliest hard evidence I have is an immigration record for George Lindley’s eldest daughter, Rose Kopaunik, dated November 7, 1925:

Canadian Immigration record for Joseph Kopaunik’s family, stating their intended destination is “Father-in-law George Coulson, Namayo, Alberta”

So it appears George Lindley had already left Plamondonville by this time, and was living in Namayo (Namao), a small village just north of Edmonton. (When they released the 1926 Prairie census last year I was able to confirm that he was actually living in Carbondale, just west of Namao, and since Carbondale was intensive coal-mining country in those days, I surmise that George Lindley had run out of money and was forced to fall back on his lifelong trade as a coal miner in his old age).

By the way, finding this immigration record was a real surprise. I had no idea Aunt Rose and her family tried to immigrate to Canada in 1925. Evidently they changed their minds and went back to Wyoming; the whole family is buried in Kemmerer.

So these are the dates of my family’s sojourn in Plamondonville: 1917 to about 1925.

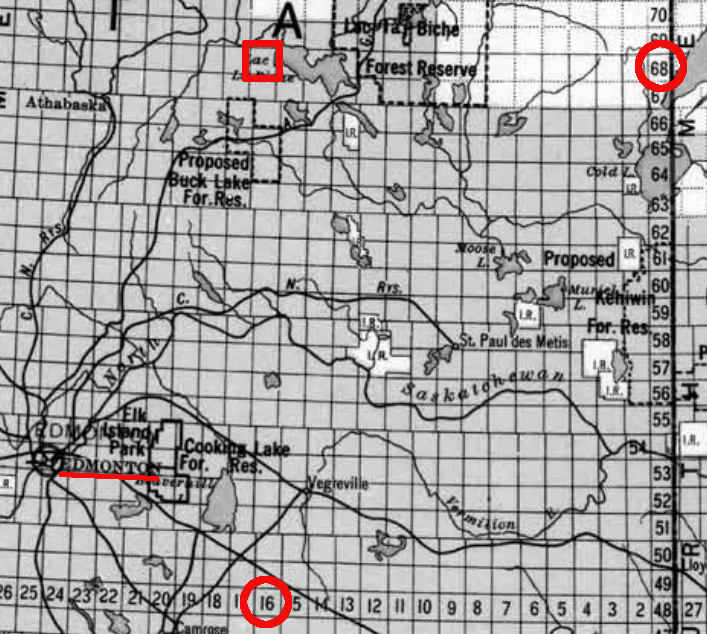

Getting back to the 1921 census… it also gave me the approximate location of George Lindley’s farm: 9-68-16-W4. This means Section 9, Township 68, Range 16 West of the 4th Meridian. You may recall we had to get into the North American survey system in some detail in Finding the Family Farm; the system used in western Canada is essentially the same as that used in the United States, just with different reference points. The baseline for the township numbering is simply the U.S. border (the 49th parallel), and the 4th Meridian is (conveniently) the border between Saskatchewan and Alberta.

This map helps to visualize the farm’s location with respect to Edmonton.

The red square to the left of Lac La Biche lies at the intersection of Township 68, Range 16. The Plamondonville townsite lies within this square and the one immediately below it.

(Notice how the squares do not line up to form perfect tidy stacks, they “jag” off to the side at intervals. This is because the survey system is a flat, square grid, but the earth’s surface is curved, so the grid must be corrected every so often, otherwise all hell would break loose.)

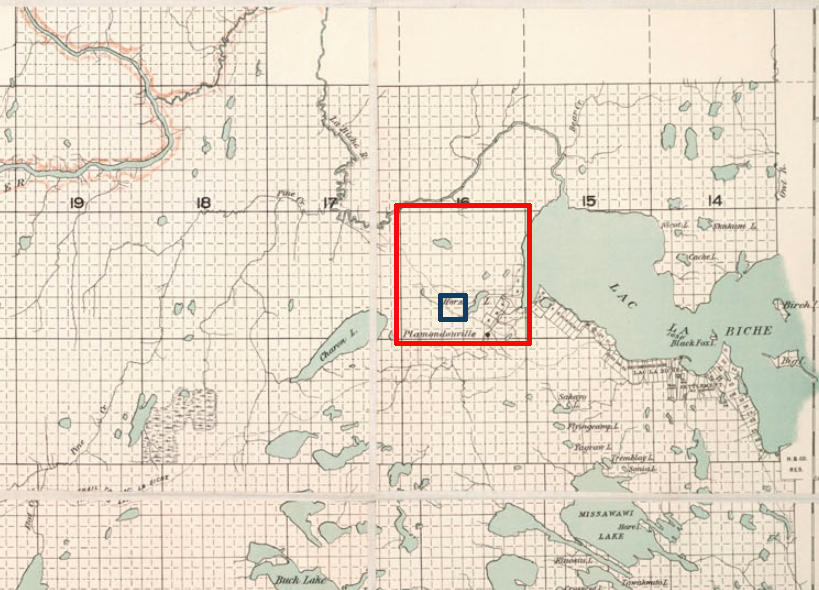

A section, recall, is a square mile of land, comprising 640 acres, and the typical land grant was a quarter of that, or 160 acres, which was what the powers that be back in the 19th century deemed was enough for a single family to work profitably. The Coulson farm was on Section #9, which is here:

This page has a good explanation of the survey system. Note that the 36 sections within a township are numbered starting at the south-east corner, whereas in Wyoming, they are numbered from the north-east corner.

Somewhere within that blue square stood the house where George Arthur suffered with the Flu in 1918 or 1919: one or two miles north-west of the Plamondon town site, and directly west of Horse Lake (Lac des Chevaux).

Now that we have narrowed the farm’s location down to the square mile, let’s see if we can find out which quarter section it was on! Where to begin?

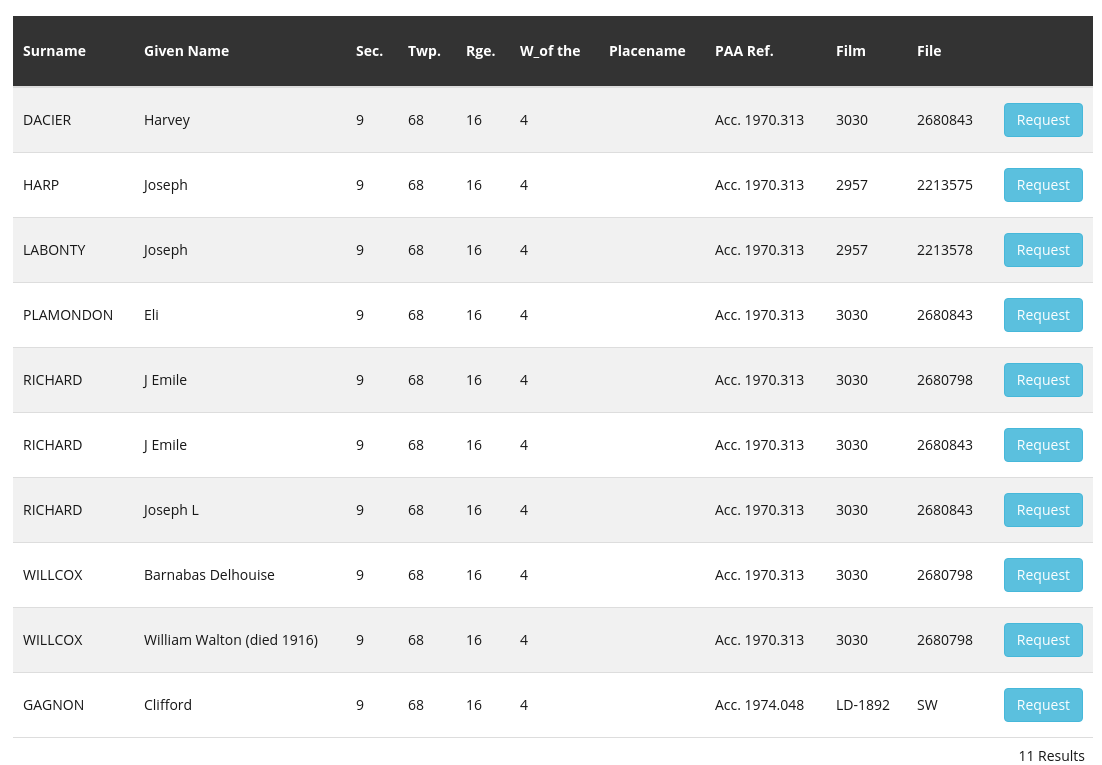

My first thought was that George Lindley might have tried to acquire the land in the form of a Homesteading grant, such as he had done in Wyoming in 1908. The Alberta Genealogical Society provides a wonderful online tool for searching the Canadian Homesteading records. This will tell us who, if anyone, homesteaded on section 9. Here’s what we get back when we plug in 9-68-16 W4:

Rats, none for Coulson. That tells me that George Lindley either bought the farm outright at the market rate, or else he was someone’s tenant.

Well, this gives us some names of homesteaders, but doesn’t tell us which quarter-section they were on or the dates. It would be nice to know these things, because then we might be able to figure out the Coulson quarter-section through the process of elimination. We could request the records, but the Alberta Genealogical Society wants $10 per record. They are also in the Provincial Archives under Accession number 1970.313, but I would have to fly to Edmonton to look, and I don’t want to wait, I want to know now.

Fortunately all the Canadian Homestead records up to 1930 have been digitized and are available on Ancestry.com. The name of the collection is Alberta, Canada, Homestead Records, 1870-1930. I was able to find all the homesteading records (except for Clifford Gagnon’s, but his record is part of the post-1930 collection that hasn’t been digitized yet, so that is outside of my range of interest) and in the process learned a little bit about my grandfather’s neighbors.

1. North-east quarter:

Joseph Labonty (Labonté) was born in Quebec. He arrived in Plamondonville from Michigan in March 1910 with his wife and 9 children and moved on to the NE quarter of section 9. He built a 459 square foot house of logs in April, and immediately broke 2 acres and got a crop in. He submitted his application for a homestead in July. By 1913 he had built a stable and granary, dug a well, and had 33 acres under cultivation. He received his land patent in 1914. He was still living there at the age of 60 with his large family as of the 1926 census, so this cannot be the Coulsons’ quarter.

2. South-east quarter:

Harvey Dacier was born in Quebec. He had most recently been employed as a civil engineer in Edmonton, but he decided to move to Plamondonville and give farming a try. He applied for a homestead on the SE quarter in 1913 and spent 10 months on the property before moving to Arizona due to ill health. He formally abandoned his homesteading claim in 1917, around the time the Coulsons arrived in Plamondon.

However, this cannot be the Coulsons’ quarter section, because in 1920 Eli Plamondon, the 18-year-old son of Nelson Plamondon, applied for a homestead on the SE quarter. He never lived there, and never built any structures on the property. His regular residence was on the neighboring Section 10; he merely used the SE quarter of section 9 for extra crops and he finally received patent for the land in 1930.

3. North-west quarter:

Joseph Harp arrived from Michigan in 1908, so he would have been a member of the original Plamondon migration. He started breaking land on the NW quarter that same year, but he didn’t start his homestead application until 1911, by which time he had 15 acres under cultivation. He occasionally went to Morinville (over a hundred miles to the south) to work on the railroad, leaving his wife and 5 children to work the farm. He received his patent in 1914 and was still living on the land at the time of the 1916 census, but by 1921 he had moved to a nearby farm. It’s possible that this is the farm that the Coulsons acquired in 1917.

4. South-west quarter:

This is the most interesting quarter. In 1912 J. Emile Richard, a clerk from Ottawa, moved to Plamondonville and filed a claim to the SW quarter. But he never took up residence there; he ran out of money and returned to Ottawa, abandoning his claim a year later.

Two months after Emile abandoned his claim, 60-year-old William Walton Willcox arrived from nearby Athabaska Landing and filed a claim to the SW quarter. He was an English-speaking Presbyterian born in Chatham, Quebec, and had recently been working in Portland, Oregon as a carpenter. He took up residence in June 1913 and built his house in September. Meanwhile he broke 6 acres and planted crops. He was new to farming, but by 1916 he had 10 acres under cultivation and had built a stable for his two horses.

Then, on September 7, 1916, William up and died. He had no wife or children, and no will, so his brother Barnabas Dalhousie Willcox came to settle his affairs. Barnabas continued with the homestead application process, and based on the improvements his brother had already made, he was awarded the patent in November, 1917. It is unclear whether Barnabas ever resided there; he does not appear in either the 1921 or 1926 census. His acquisition of the land title coincides approximately with the Coulsons’ arrival in Plamondon, so it is possible that he sold his brother’s property to George Lindley, and then vanished.

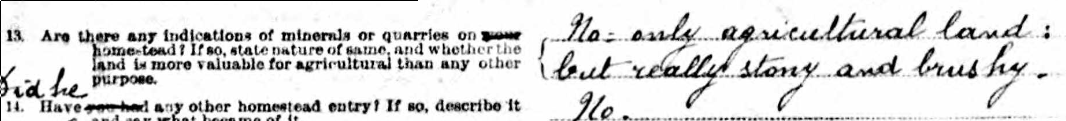

I’m not sure which quarter I like better as candidate to be the Coulson home: north-west, or south-west. The houses were of comparable size: Joe Harp built a 340 square foot house (which must have been tiny for his family of 7) while William Willcox’s house was slightly bigger at 352 square feet. Barnabas Willcox makes a comment on his patent application that swings me in favor of the latter: in response to a question about mineral resources on the land, he replies “No, only agricultural land, but really stony and brushy.”

That would be just my great-grandfather’s luck, to be stuck with a piece of stony, brushy land.

More about the history of Plamondon can be found in this book, which you can read online: From Spruce Trees to Wheatfields: Plamondon 1908-1988

So interesting! Thank you for this, Fred. Our local history is a precious thing. I always l0ve to learn more. And it is so important to remember the hardworking and courageous souls who built our modern society out of the wild bush in the toughest circumstances…