We don’t know for sure, but we think that George Lindley Coulson and his step-father Tom Henson appear in this photo of coal miners of Rotherham, Yorkshire because it used to be in the possession of George’s half-sister Helen Coley. From the collection of Elizabeth I. Coley and used here with the kind permission of William Lindley Coley III.

My great-grandfather George Lindley Coulson grew up working in the coal mines of west Yorkshire. When he arrived in North America with his wife and family around 1890, he found employment in the coal mines of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. That was about the time that the Wyoming coal boom was starting, and he was drawn to Cambria– a thriving boom-town north of Newcastle, Wyoming, that no longer exists– to work in those coal mines in the mid-1890’s (possibly as early as 1892).

My point being, George Lindley was a coal miner with an urban background, and none of the oral family lore I know of indicates he had any aptitude for or interest in farming. I was therefore surprised to discover, while researching him and his family, that after spending a few years working in the coal mines of Wyoming, he decided to try his hand at homesteading!

Homesteading, as codified in the 1862 Homesteading Act, was intended to implement the old Jeffersonian ideal of a nation of citizen-farmers tilling the land in small family-sized plots, an ideal that was part and parcel of the American Dream as it was perceived throughout much of the 19th century. Another purpose of the Act was to curtail land speculators who would buy up land and sell it later at profit– the government wanted to bring as much land as possible under cultivation, and make it affordable and attractive to immigrants, and speculators stood in the way of this kind of economic progress.

To deter speculators, a prospective homesteader would be granted a quarter-section of land (160 acres) at a nominal cost, but with certain conditions attached. If, at the end of a 5-year period, the homesteader could prove he or she had lived on the land continuously and had brought it into production (or “improved” it), the government granted title to that land free and clear to do with whatever the homesteader pleased. If desired the land could be sold at a handsome profit, but the Government hoped that the homesteader would stay and put down roots, having invested so much sweat-equity in the land already.

Alas, it appears that my great-grandfather did not enter into his homesteading adventure with the purist of Jeffersonian intentions. After weighing the evidence I am compelled to admit that he was, in fact, a land speculator with no interest in improving the land or putting down roots in the Wyoming soil; he was in it purely for the money (which is a more modern version of the American Dream, you might say). Since there is nobody left in the family who remembers our brief ancestral homesteading period, all I have to go on are the homesteading records themselves along with what I can find in the newspapers. So here, with a big dollop of my own speculation, is the evidence.

My great-grandfather’s proper name, according to his baptismal record, was George Lindley Coulson, but he didn’t always put the ‘d’ in Lindley and he also went by Linley G. Coulson. He was also known as “Splint” and he appears to have been a bit of a local character because the newspapers in Crook and Weston Counties frequently refer to him with that nickname. He also sometimes appears with the common misspelling of our name, Colson. These are things to keep in mind when reviewing the records.

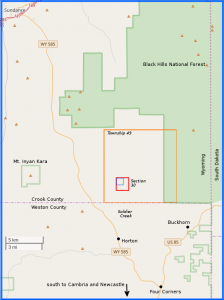

In 1898 George staked his claim to the Northwest Quarter of Section 30 in Township 49, Range 61, West of the 6th Principal Meridian — Also known as NW¼ 30-49-61 W6. That’s in the northeast corner of Wyoming, a few miles from the South Dakota border, technically part of the Black Hills (and just outside the bounds of the Great Sioux Reservation established by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868), and within sight of the sacred Lakota mountain Inyan Kara, a mountain that “spoke”, perhaps because it was at one time full of unmined coal and spontaneous coal fires deep underground made the earth groan, a fact that was noted by indigenous peoples and early European fur traders.

Here’s where that is on the map.

The orange square represents Township 49 of Range 61. The word “township” here has nothing to do with towns. It’s just a name for one of the subdivisions in the system of land surveying that is used in the U.S. and Canada.

The orange square represents Township 49 of Range 61. The word “township” here has nothing to do with towns. It’s just a name for one of the subdivisions in the system of land surveying that is used in the U.S. and Canada.

The survey nomenclature means that this square is the 61st township counting west from the 6th Principal Meridian, a north-south line that runs from the northern border of Nebraska, through Kansas to the northern border of Oklahoma. It is also the 49th township counting north from the 6th Meridian’s associated baseline, which is an east-west line running along the northern border of Kansas, through Colorado to the Utah border. To visualize this system, this map from Wikipedia might help.

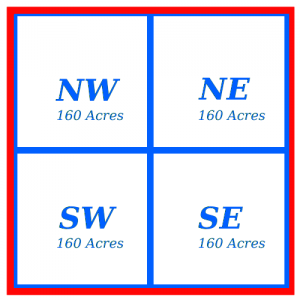

Each township is divided into 36 sections, numbered sequentially from the northeast corner of the township. Each section contains one square mile, or 640 acres. Sections are further subdivided into 160-acre quarter-sections. A quarter-section was the basic land-grant unit for the homesteading system through the 19th century and into the 20th.

Each township is divided into 36 sections, numbered sequentially from the northeast corner of the township. Each section contains one square mile, or 640 acres. Sections are further subdivided into 160-acre quarter-sections. A quarter-section was the basic land-grant unit for the homesteading system through the 19th century and into the 20th.

Township 49 is the orange box on the map at the right, and Section 30 is the red box within township 49. The blue box inside of section 30 is the northwest quarter-section which constituted George Lindley’s claim.

Within each quarter-section there are further divisions (“lots”) of 40 acres each. We’ll talk about those later, because they are a source of some confusion, as we shall see.

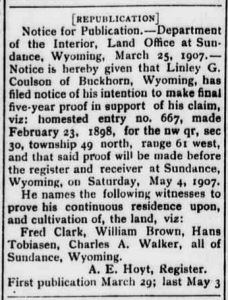

How did I first learn about the Coulson Homestead? I stumbled upon it accidentally when combing through the old newspapers that are archived by the State of Wyoming (Wyoming Newspapers, newspapers.wyo.gov). The following notice was published in the Crook County Monitor (based in Sundance, Wyoming) on Friday, May 3, 1907.

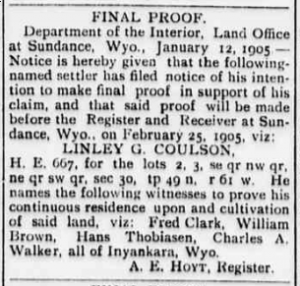

Notice for Publication – Department of the Interior, Land Office at Sundance, Wyoming, March 25, 1907.- Notice is hereby given that Linley G. Coulson of Buckhorn, Wyoming, has filed notice of his intention to make final five-year proof in support of his claim, viz: homestead entry no. 667, made February 23, 1898, for the nw qr, sec 30, township 49 north, range 61 west, and that proof will be made before the register and receiver at Sundance, Wyoming, on Saturday, May 4, 1907.

Notice for Publication – Department of the Interior, Land Office at Sundance, Wyoming, March 25, 1907.- Notice is hereby given that Linley G. Coulson of Buckhorn, Wyoming, has filed notice of his intention to make final five-year proof in support of his claim, viz: homestead entry no. 667, made February 23, 1898, for the nw qr, sec 30, township 49 north, range 61 west, and that proof will be made before the register and receiver at Sundance, Wyoming, on Saturday, May 4, 1907.

He names the following witnesses to prove his continuous residence upon, and cultivation of, the land, viz: Fred Clark, William Brown, Hans Tobiasen, Charles A. Walker, all of Sundance, Wyoming.

A. E. Hoyt, Register. First publication March 29; last May 3.

This gives us quite a bit of information. First it indicates that George Lindley and his family were living in Wyoming as early as 1898. I am pretty sure they were there much earlier than that, but this is the earliest solidly dated documentation that I have so far.

Second, it tells us the names of some of George’s friends and neighbors, people who were willing to vouch for him and state that he had been living there for at least 5 years. One significant name I notice is Fred Clark, who also had a homestead in the Inyan Kara neighborhood not far from the Coulsons. I know from my previous research that George’s next-to-last son Frederick Clark Coulson was born in 1902. Apparently, George named his son after his friend and neighbor, Fred Clark! I am especially interested in this connection because I myself am named after this Uncle Fred, who died before I was born… so now I know where my name comes from. My research into the Crook County pioneer Fred Clark, who had such an impact on my great-grandfather, will be a blog post for another day.

Third, it gives us the survey designation of the property (NW 30-49-61). Since historical homesteading records are pretty well documented, this allows us to look up George’s claim on the U.S. Bureau of Land Management database.

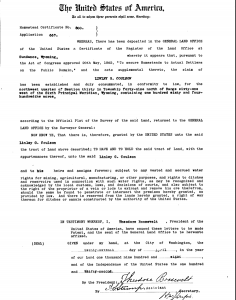

Sure enough, here we find the actual patent that was issued to George on April 27, 1908, a year after he made his “final proof” application:

Homestead Certificate No. 800.

Application 667.

WHEREAS, There has been deposited in the GENERAL LAND OFFICE of the United States a Certificate of the Register of the Land Office at Sundance, Wyoming, whereby it appears that, pursuant to the Act of Congress approved 20th May, 1862, “To secure Homesteads to Actual Settlers on the Public Domain,” and the acts supplemental thereto, the claim of

LINLEY G. COULSON

has been established and duly consummated, in conformity to law, for the northwest quarter of Section thirty in Township forty-nine north of Range sixty-one west of the Sixth Principal Meridian, Wyoming, containing one hundred sixty and four-hundredths acres, according to the Official Plat of the Survey of the said Land, returned to the GENERAL LAND OFFICE by the Surveyor General:

NOW KNOW YE, That there is, therefore, granted by the UNITED STATES unto the said Linley G. Coulson the tract of Land above described, TO HAVE AND TO HOLD the said tract of Land, with the appurtenances thereof, unto the said Linley G. Coulson and to his heirs and assigns forever; subject to any vested and accrued water rights for mining, agricultural, manufacturing, or other purposes, and rights to ditches and reservoirs used in connection with such water rights, as may be recognized and acknowledged by the local customs, laws, and decisions of courts, and also subject to the right of the proprietor of a vein or lode to extract and remove his ore therefrom, should the same be found to penetrate or intersect the premises hereby granted, as provided by law. And there is reserved from the lands hereby granted, a right of way thereon for ditches or canals constructed by the authority of the United States.

IN TESTIMONY WHEREOF, I, Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States of America, have caused these letters to be made Patent, and the seal of the General Land Office to be hereunto affixed.

GIVEN under my hand, at the City of Washington, the twenty-seventh day of April, in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and eight, and of the Independence of the United States the one hundred and thirty-second.

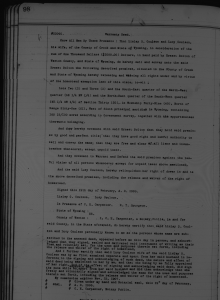

This transaction is recorded in the BLM Tract Book for Township 49. It’s a little hard to read, but the record of George’s claim is the 6th entry from the bottom of the page. It indicates how he bought the 160 acres on February 23, 1898 for $1.25 per acre with a down payment of only $16, and indicates that the final patent was issued ten years later on April 27, 1908, as we have already noted.

Well, that was quite a find for me. George received this parcel of land, to have and to hold forever! And I, being one of his “heirs and assigns”, might well be owning that land today, if history had taken a different turn.

But this is where things start getting a little weird.

First of all, before George received title to his land in 1908– in fact, before he even made his application for “final proof” in 1907– he sold the land.

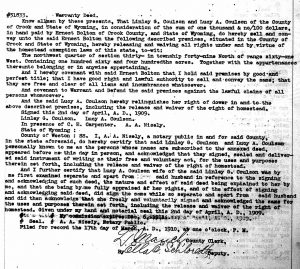

That’s right. He sold the land to one Ernest Bolton for $1,000 on February 19, 1906, according to the Warranty Deed at the right, which I found on microfilm at the Wyoming State Archives in Cheyenne.

Since homesteading was intended to be a family affair, the homesteading laws recognized the rights of the wife– that way the husband could not just sell the land and abandon his family without resources to fend for themselves. The fact that the Coulsons believed this land was theirs under the Homestead Act is evidenced by the final paragraph, where my great-grandmother Lucy has to explicitly sign her Right of Homestead away:

And I further certify that said Lucy Coulson wife of the said Linley G. Coulson was by me first examined separate and apart from her said husband in reference to the signing and acknowledging of such deed, the nature and effect of said deed being explained to her by me, and that she being by me fully appraised of her right, and of the effect of signing and acknowledging said deed, did sign the same while so separate and apart from her said husband and did then acknowledge that she freely and voluntarily signed and acknowledged the same for the uses and purposes therein set forth, including the release and waiver of the right of homestead.

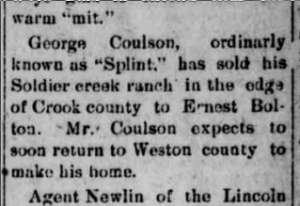

The land sale was such a notable event that the newspaper in Newcastle south of Cambria saw fit to run a tiny news item about it.

So… George and Lucy sold the land more than two years before they legally owned it. This, on the face of it, sounds like fraud. But then again, maybe not… here’s an added complication: the parcel of land that George got title to in 1908 is not exactly the same as the one he sold to Ernest Bolton in 1906.

Remember, the land described in the Patent that was granted in 1908 was described as NW¼ 30-49-61 W6. However, the land that Mr. Bolton bought in 1906 is described as Lots 2 and 3 and the southeast quarter of the northwest quarter and the northeast quarter of the southwest quarter of section 30 in township 49, north of range 61. Whew. That’s gonna take some decoding.

Remember how a section is divided up into quarter-sections of 160 acres each. George’s quarter section, which he ultimately received the patent for, is the northwest quadrant.

Remember how a section is divided up into quarter-sections of 160 acres each. George’s quarter section, which he ultimately received the patent for, is the northwest quadrant.

Each quarter-section can itself be divided into 40-acre lots. These are designated as at the right. For example, the NWNW lot is sometimes referred to as “northwest quarter of the northwest quarter”, and SESW can be referred to as “southeast quarter of the southwest quarter,” and so forth. It’s a little confusing but you get the idea.

Each quarter-section can itself be divided into 40-acre lots. These are designated as at the right. For example, the NWNW lot is sometimes referred to as “northwest quarter of the northwest quarter”, and SESW can be referred to as “southeast quarter of the southwest quarter,” and so forth. It’s a little confusing but you get the idea.

Lots can also be designated by lot number, and there seems to be no universal way of numbering the lots. This is how I think the lot numbering goes, but I could be wrong.

That means that the land George sold to Mr. Bolton in 1906 (Lots 2 and 3 and the southeast quarter of the northwest quarter and the northeast quarter of the southwest quarter of section 30 in township 49, north of range 61) are the lots in green:

That means that the land George sold to Mr. Bolton in 1906 (Lots 2 and 3 and the southeast quarter of the northwest quarter and the northeast quarter of the southwest quarter of section 30 in township 49, north of range 61) are the lots in green:

…What on earth is George doing trying to sell a lot in the Southwest Quarter of section 30? His original homestead claim made no mention of that at all!

OK, and things get even messier. Remember how a homesteader is supposed to post a “final proof” to their claim in the newspaper before the patent can be issued? Well, George did that for these four parcels of land in 1905. It’s identical to the one we saw above (from 1908), except it references the odd grouping of parcels that appear in the bill of sale to Bolton in 1906: Lots 2 and 3 and SENW and NESW of 30-49-61!

I should add that George did not at any time receive a patent for the land hereunto described.

I think I have a workable explanation for this mess, and I think the clue lies in a clause attached to the final patent we looked at above:

And there is reserved from the lands hereby granted, a right of way thereon for ditches or canals constructed by the authority of the United States.

I’ll bet that when George and his family moved on to the northwest quarter of Secton 30 in 1898, he discovered that he was unable to use the northwest 40 acres of his claim because the government needed it for a ditch or canal or right-of-way of some kind. So, he started using the southeast lot of the quarter-section immediately below his as (to him) just compensation, since nobody had claimed it yet. Maybe he had a handshake agreement with some government official that this was “fine”. After he had lived there for more than 5 years and posted his “final proof” in the paper, maybe he had forgotten all about it. Or maybe he thought the government had recorded the change in their record book. Maybe he thought his patent was a shoe-in, so he went ahead with the sale of the land to Bolton without waiting for his homesteading patent to be issued.

(In fact, there is a hastily-scrawled notation in red ink in the Tract Book that I can scarcely make out, but it seems to say something like “Amended by XXX July 2, 1902…” and the rest is indistinct. Part of the scrawl looks like “SW 1/4”, so perhaps this is a reference to George’s use of the NESW lot. Can you make out what it says?)

Imagine the bureaucratic nightmare when George and Ernest Bolton discovered the sale could not go through, because George had no legal claim to the the lot in the southwest quarter! George probably had to start his paperwork all over again. It took 3 more years for the mess to be sorted out.

There’s a happy ending to this story– We find another warranty deed in the county records, documenting George Lindley Coulson’s sale of land to Ernest Bolton (again) for $1,000, this one dated April 2, 1909– a year after George received his land patent. This time, it seems, he wasn’t taking any chances! This bill of sale is essentially identical to the one in 1906, except it refers to the northwest quarter of Section 30 in its entirety, just like it appears on George’s patent. We can only assume that the 1906 sale was cancelled, and Bolton got his money back.

George Lindley made a tidy profit on the transaction, despite the red tape and misunderstandings he no doubt endured. For an initial investment of $16, he eventually walked away with $1,000 in 1909 U.S. dollars. But the happy ending was short-lived… Shortly after this sale was transacted, George and Lucy and their younger children– Mary, Maggie, Fred, and little George Arthur– pulled up stakes and headed for Canada in an adventure that would turn into disaster for the family. More on that in a future post.

As for Ernest Bolton, it appears he did put down roots in the Wyoming soil. I found newspaper references to him as an “industrious young farmer”, and a mention of him digging a mine on his property. The last trace I have of him was a notice that he was drawing an old age pension from Crook County in 1932.

Pingback: An Unlikely Farmer | Fred's Blog

You’ve got a real fascinating investigation! It was interesting to read your notes. Thanks =)