Here’s an interesting story that I found buried in the parish records from Rozdziele, my ancestral village on the north slope of the Carpathian Mountains. Today the village lies within the borders of Poland, but at the time these events took place it was part of Austrian Galicia. Some of what follows is the product of my own fertile imagination, but I’m pretty sure I have uncovered an unusual love story in the pages of these dusty old metrical registers.

This man is Metro Telep. He was born in Rozdziele in 1882 and worked as a coal miner in Fernie, British Columbia his whole life. His many descendants are to be found scattered across western Canada. He was my great-grandfather’s half-brother; they grew up together and must have emigrated to Canada around the same time. I knew him as “Grandpa Telep”, but nobody in my immediate family was certain of our relationship to him until I started delving into the Rozdziele records a few years ago. He is the only family member I ever met who had a living connection to the old country.

This photo was taken in 1975. We were on our way back from an Easter break trip to visit my dad’s brother’s family in Richmond on the coast, and we stopped in at Grandpa Telep’s place in Haney to help with the campaign to convince him to move into a nursing home. Metro had been living by himself after his wife Dora died (Theodosia Nowak, 1886-1966, also born in Rozdziele), and his children were very concerned about him because he was starting to slip. I remember having to wait outside because there wasn’t room for the kids inside the tiny house, and the adults had to stand in the kitchen and talk to Grandpa Telep because he did not have any chairs, for some reason. Here he is holding court seated on the oven door, in front of the firewood that he chopped and stacked himself. (Looking a little closer at that pile, maybe that’s what was left of his chairs.) He eventually did move into a nursing home, and a few years later he died at the ripe old age of 96.

But this story isn’t about Grandpa Telep, it’s about his great-grandmother, Anna Barszcz (barszcz, барщ, is the Rusyn form of the word for borsht, beet soup). When she was born in 1791 her father went by the name of Andreas Paulak, but Barszcz must have been a family alias because by the 1810’s Andreas and his children appear in the records with the Barszcz surname. (You can read more about this common dual-surname phenomenon in this article, The Dual Identity of the Lemko Villager.)

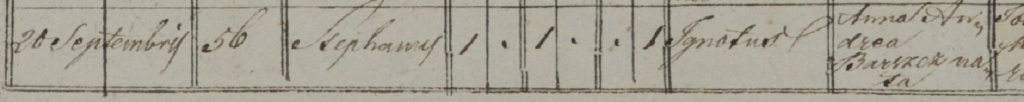

In 1814 Anna, 23 years old, unmarried and living in her father’s house, had an illegitimate son, Stephanus. The birth record gives the father as Ignotus— “unknown”.

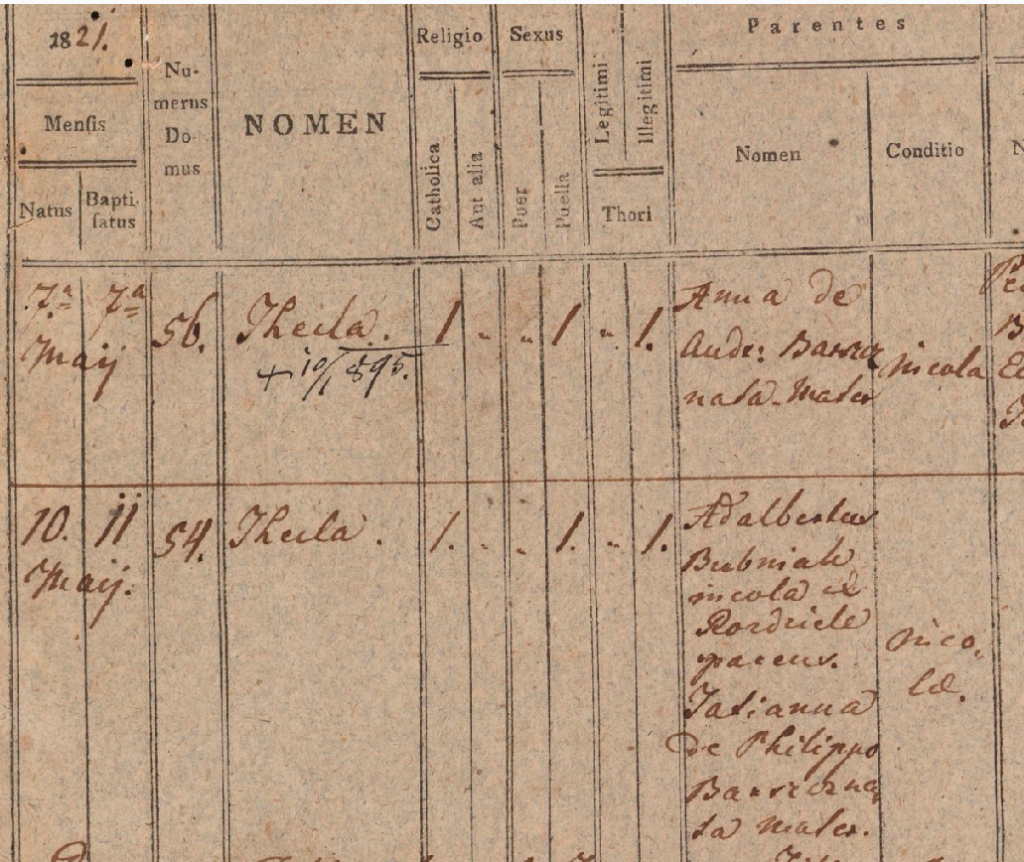

Seven years later (May of 1821) Anna gave birth to a second illegitimate child, Thecla. Again, no father is indicated.

I include as an aside the birth record following Thecla’s: the next baby born in the village was also named Thecla, and her parents, Adalbert and Tatianna Bubniak, appear to have been next-door neighbors to Andreas Barszcz. I believe that Andreas and Tatianna were cousins, although I haven’t nailed down their exact relationship yet. I draw your attention to the Thori column– Thecla Bubniak is marked as illegitimate too! (Thori illegitimi means “[born] of an illegitimate bed”.) The curious case of Adalbert Bubniak’s illegitimate children is something I have written about elsewhere. It’s of interest to me because Adalbert and Tatianna are my great-great-great-great grandparents, and the families of Adalbert and Andreas remained tightly linked across several generations. But I digress. Getting back to the story at hand…

Ten years pass. Anna’s father Andreas Paulak/Barszcz died in 1831 at the age of 83.

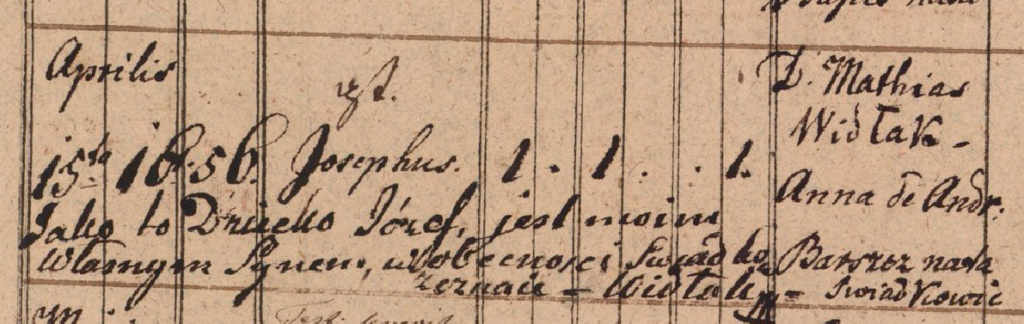

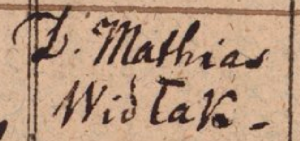

Then in April of 1833 Anna had a third child, Josephus. She was now 42 years old, and still living in her late father’s house, which was now densely populated with members of her extended family. Josephus, like his siblings, was marked illegitimate in the record book. But the significant thing about his birth record is that, while he is illegitimate, he does have a father: a certain Mathias Widłak signed a statement on the record, declaring

Jako to dziecko Józef jest mojim własny: “This child Jozef is my own.”

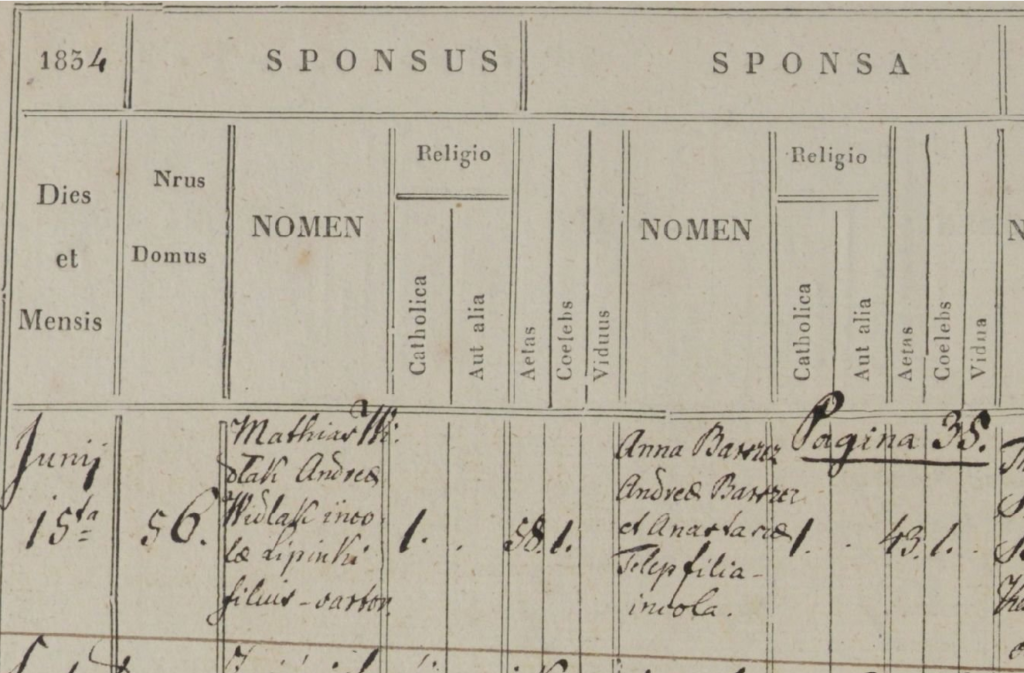

Little Josephus survived for only 5 weeks. But guess what? In June of 1834, a year after they laid him to rest, Anna and Mathias got married!

These are all the historical facts of the case that I have been able to gather. What to make of it all? Here is where my romantic imagination kicks in.

Mathias is interesting because when he appears in the record books, there is often a “D.” in front of his name. That must stand for Dominus, “Lord”, or Pan in Polish, which means he was of noble birth. However, his occupation on the marriage record is given as sartor, tailor. So he must have been of the landless gentry (szlachta) who had to work for a living. It’s also notable that his home was in Lipinki, a town about a kilometer north of Rozdziele. Lipinki and Rozdziele had close historical and cultural ties, but their church administration and religious life were quite distinct: Lipinki was Roman Catholic and predominantly Polish, whereas Rozdziele’s population was Lemko and its church was under the jurisdiction of the Greek Catholic Eparchy of Przemyśl, which, while technically acknowledging the Pope in Rome as its supreme head, in form and function more closely resembled the Orthodox Church.

This is what I think: I think that Pan Mathias was a traveling haberdasher who would come to Rozdziele regularly on business, and on one of his visits he fell in love with a Lemko peasant girl named Anna. But alas, there was some obstacle to their happiness. Perhaps there was something about Mathias that her father didn’t like… Was it that he was Polish? Roman Catholic? a szlachta? I don’t know. Let’s just suppose that Andreas didn’t like this smooth-talking Polish gentleman, and he forbade the marriage.

But love will find a way. The couple would meet secretly whenever Mathias came to the village, and over a span of almost 20 years they managed to have three children out of wedlock.

While illegitimate children were by no means uncommon in the village, there was a definite social stigma attached to them. There can be no doubt that Anna’s father disapproved: his daughter was bringing more mouths to feed into his household, and probably damaging his reputation among his neighbors. Their relationship must have been fraught. I wonder what promises Mathias made to her, throughout those difficult years.

Finally, the stern old father died, and Anna and Mathias were able to wed at last. Mathias, nearly 60 now, did right by his children. Both Stephanus and Thecla are surnamed “Widłak” in later records, which tells me that he formally adopted them. This would have been a very big deal in those days, because to be a bastard in that society was a mark of shame that was very difficult to overcome.

What happened next? Anna died in 1847 in the very same house where she had been born 56 years earlier. But what happened to Mathias? I have no record of his death. Anna’s death record makes no mention of her being a widow, so Mathias must have outlived her. Did he abandon Anna after their marriage, having satisfied his obligations as a father and his honor as a gentleman, but preferring to live in the bourgeois comfort of his own home town? Or did they live out their final years together in marital bliss, in Anna’s ancestral home? Did Pan Mathias give up tailoring and take up the peasant life?

I would have a clue if I could see Mathias’ death record. If he died in Rozdziele, news of his death would have reached the parish priest in Lipinki and it would have been recorded in the Lipinki book, with the annotation that he died in Rozdziele. But the Lipinki records have not yet been digitized by the Polish National Archives, so I shall have to wait and see. Meanwhile, I will assume that the story has a happy ending.

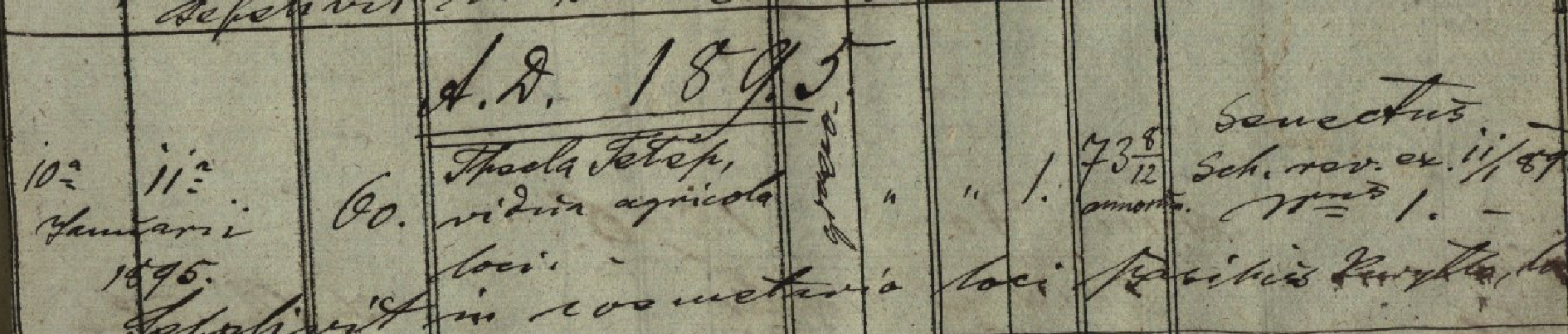

Thecla herself lived a long time and was able to watch her grandson Metro grow into a young man. He was 13 when she died in 1895, and he would be off across the big water to Ameryky within a few years. Did Thecla ever tell her grandson the story of her parents’ secret passion?

I wonder if Grandpa Telep knew that he was descended from Polish aristocracy.