When I was driving through Havre, Montana a while back I decided to stop at the public library to see if they had any books on local history. I wanted to investigate a story I had heard that my grandfather’s sister, my notorious Aunty Mary, had worked at a hotel there as a girl.

It turns out the library does have quite a rich section dedicated to local history and genealogy which I could have spent days perusing. I didn’t discover anything about Aunty Mary’s hotel but one thing I did make note of before the library closed was an ancient dusty set of books containing Montana marriage registrations going back to the start of the 20th century. I wished I could have taken it home with me because I had a feeling it would come in handy someday.

Fortunately there was no need to walk off with it. The reason such valuable old records are lying out in the open is that they were digitized and indexed long ago by the Mormons and they are now available as the Montana, County Marriages, 1865-1993 database on FamilySearch.org. Searching through those marriage registrations, as well as census records from those days, has taken my research to a new level. Another resource I’m putting to good use is the free collection of old newspapers hosted by the Library of Congress.

One interesting character I traced through the years was John C. “Bear Paw Jack” Griffin. Here’s an excerpt from his obituary, which appeared in the Choteau Acantha on September 10, 1913:

During the early eighties Mr. Griffin came to Fort Assinniboine and had the contract for hauling wood to the post for some time. About 1888 or 1889 he settled on a ranch in the Bear Paw mountains, about 25 miles south of Havre, where he has since resided. As the years rolled by he increased his land holdings and stock interests until at this time he has over two thousand acres of the finest land along the Clear Creek valley, besides hundreds of head of cattle and horses.

In the 1910 Census I found Jack Griffin’s family living in Clear Creek as the obituary states. His wife, Mary T. Griffin, is identified as French Canadian, born about 1862 in Canada. I used the list of children in the household (the eldest being Nathaniel, born about 1886) to trace the family back to the 1900 Census. There the head of the household is identified as Mary T. Davis, born in Canada in 1862. This has to be the same Mary T. as is in the 1910 Census. All the children are surnamed Griffin and it says they had been married 20 years; it seems Mary and Jack must have had a common-law marriage.

Sure enough, I found their actual marriage registration in that database comprising the marriage registers I saw in the Havre library. In 1902, after more than 20 years of living as man and wife, John C. Griffin married Mrs. M. T. Davis, previously married and divorced. Her maiden name was Paul and she was born in Manitoba, Canada. Her race is listed as “Half-breed”, which is what they were calling the Métis back then.

The census says that Mary T. immigrated to the U.S. in 1879 (aged 17). It says Jack immigrated in 1866 (aged 16). I wonder whether any of the children belonged to Mary’s first marriage with this Davis fellow. If we take the statements on the census at face value then I suspect Mary left her first husband Mr. Davis in Manitoba in 1879 and headed south, meeting Jack when he was hauling wood to Fort Assinniboine in 1880; that is the year of the birth of her first (known) daughter, Betsy. It’s hard to say since Mary and Jack weren’t actually married until 1902 and her first marriage didn’t leave a paper trail that I have found.

The eldest son Nathaniel was a bit of a troublemaker, according to a snippet I found in the Fort Benton newspaper:

The River Press, May 29, 1912

A news item from Havre reports the escape of Nat Griffin from the Hill county jail. The prisoner was being held for trial on a charge of cruelty to animals at Box Elder, and conviction would have given him a term in the penitentiary.

Old Bear Paw Jack died the following year (September 1913, as we have seen). Then I found, again in those Montana marriage registers, Mary T. Griffin of Havre marrying one Martin Nelson, a 53-year-old Norwegian immigrant.

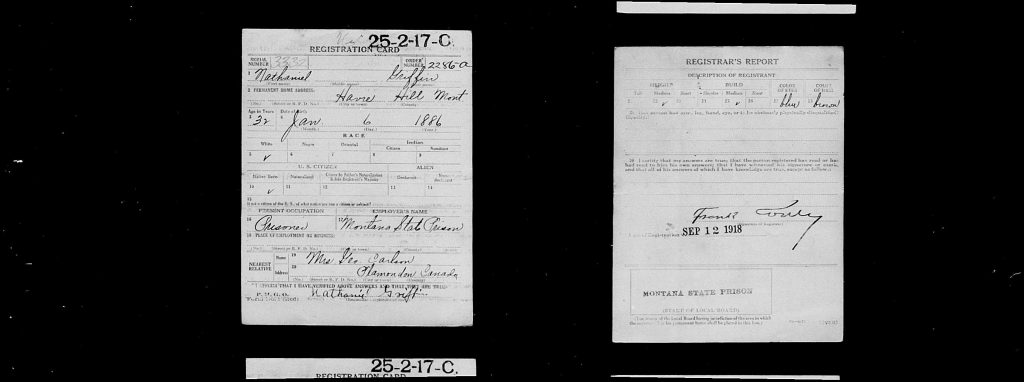

After that I lose track of Mary and Martin Nelson. Nathaniel pops up in the Montana State Penitentiary records in 1916, when he was sentenced to 2-8 years for Grand Larceny. In September 1918 Nathaniel, despite being in prison, had to register for the Draft, since the U.S. Army was desperate for recruits and had to start reaching pretty low to satisfy The Great War’s unquenchable thirst for human life. Mercifully Germany and Austria were collapsing at that point and the war was over two months later, so it doesn’t look like Nathaniel got to see action.

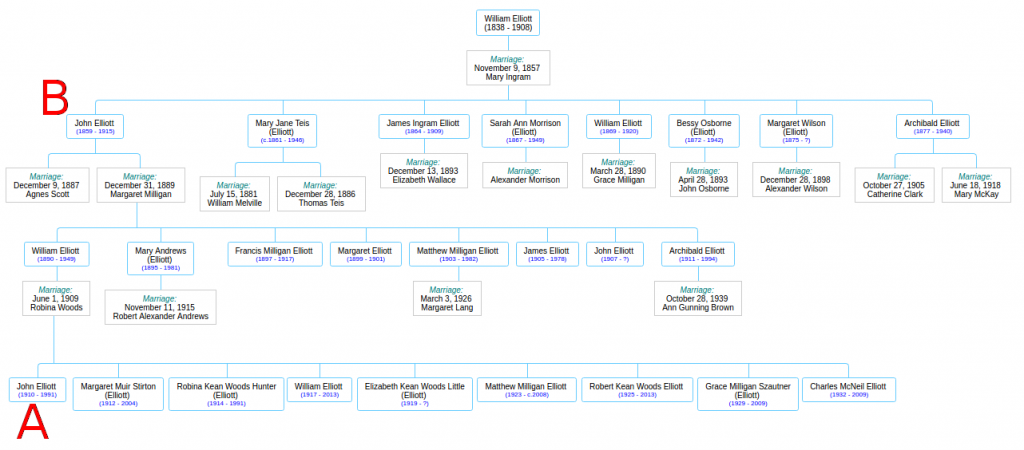

Interesting stuff, but this is not a story about Bear Paw Jack or his wayward son. Those people are not in my family tree at all. No, this is a story about the identity of my great-grandfather’s second wife. Let’s back up a bit.

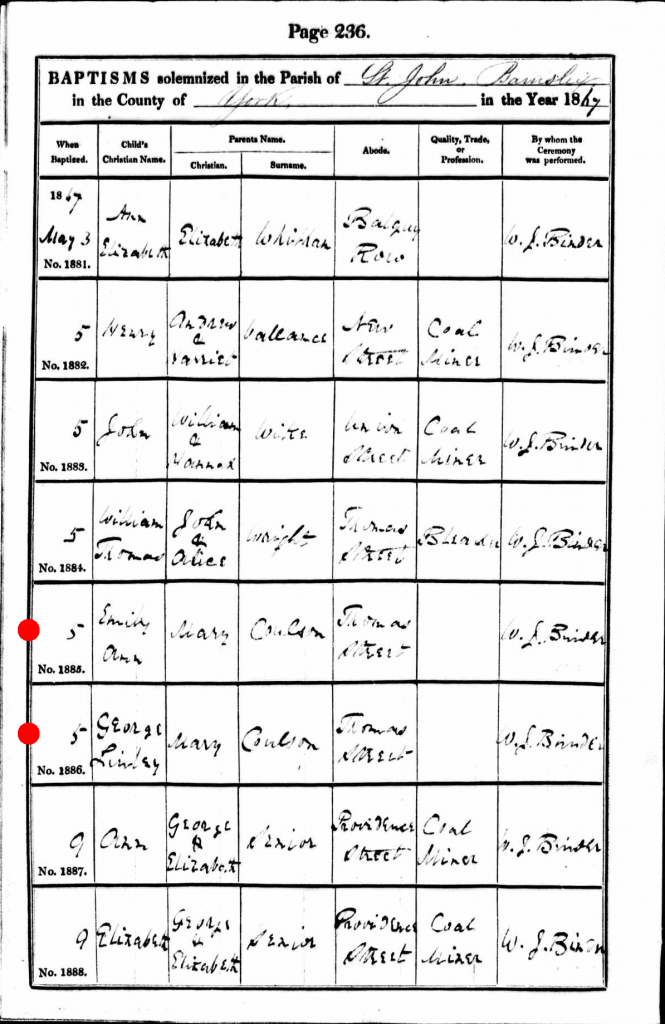

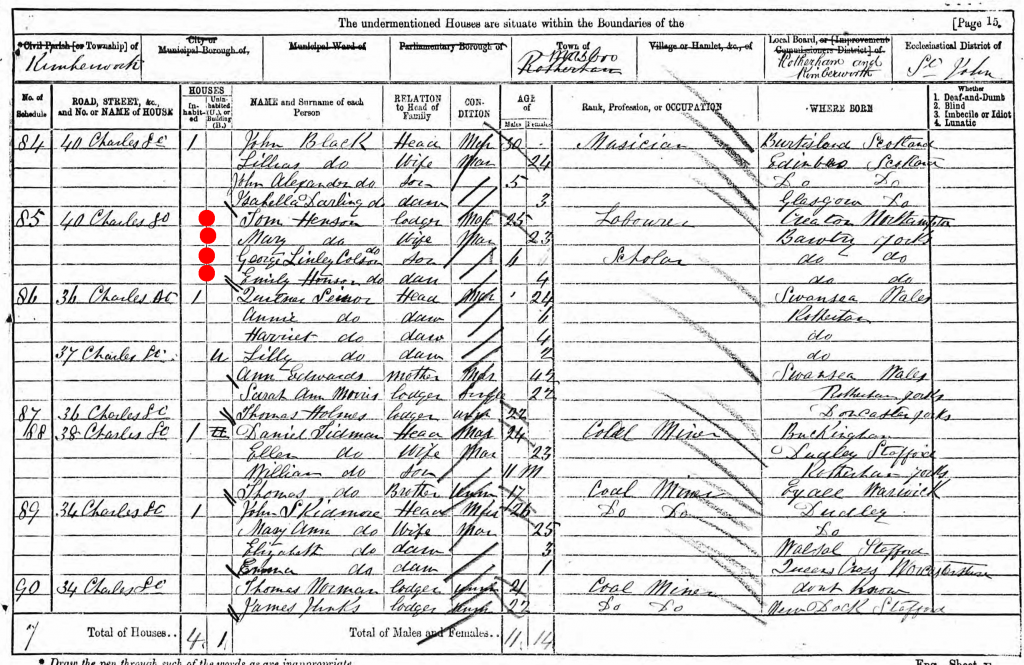

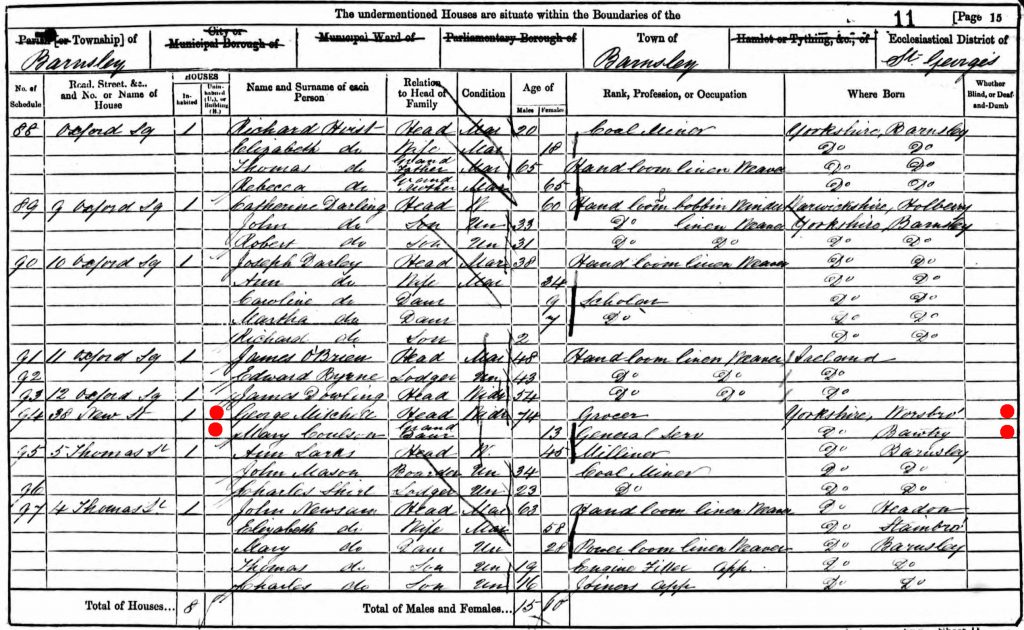

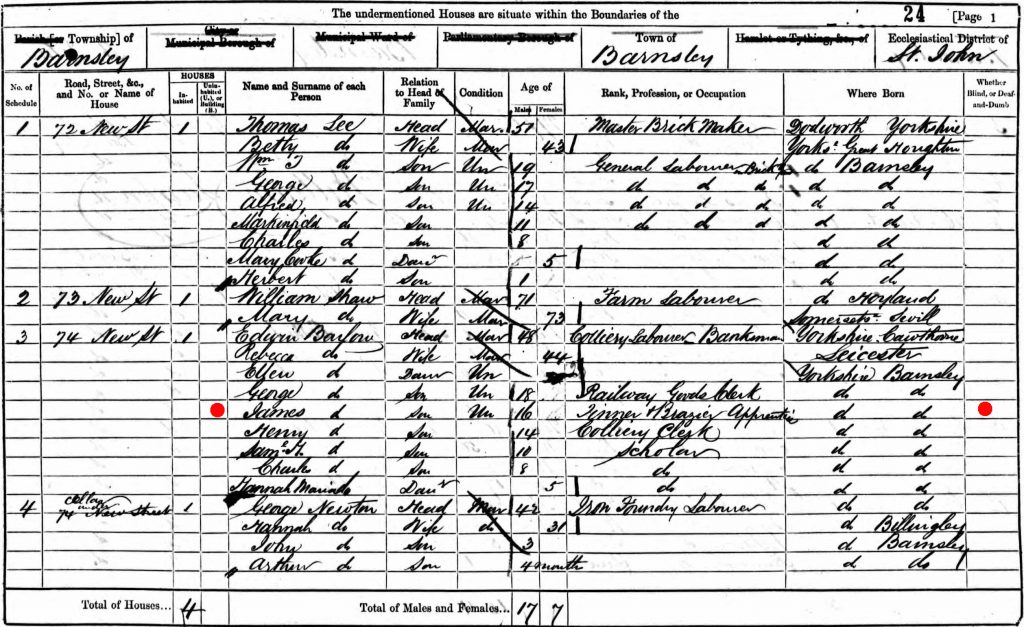

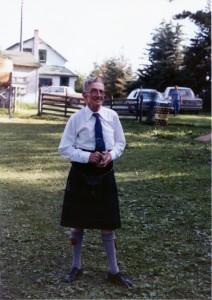

My great-grandfather George Lindley Coulson was born in 1864 and grew up in the coal mines of Yorkshire. He married Lucy Ann Scarlett, a tiny but tough woman from Staffordshire. The story of their epic journey from England to Pittsburgh to Wyoming and finally to Saskatchewan will have to be told another day. They stopped for a while in Havre, Montana, and that’s where their daughter (my Aunty Mary) stayed to work in the hotel. The rest of the family continued on, crossing the extremely porous U.S.-Canada border in the summer of 1911 (on foot, walking alongside their livestock). Almost as soon as they arrived at Fort Walsh, Saskatchewan, Lucy, aged 44, dropped dead from tuberculosis and pneumonia. She had had two miscarriages along the way, and she was exhausted. She lies buried in the Northwest Mounted Police cemetery at Fort Walsh, one of the few civilian graves to have a real headstone. She was highly esteemed by all her children. Fifteen-year-old Aunty Mary had to come racing up from Havre in her employer’s buckboard to take charge of the family, since George Lindley, having gone to Maple Creek to buy a casket for his dead wife, wound up spending the money on a drinking binge while his wife’s body lay back at the Fort ripening beneath the hot August sun.

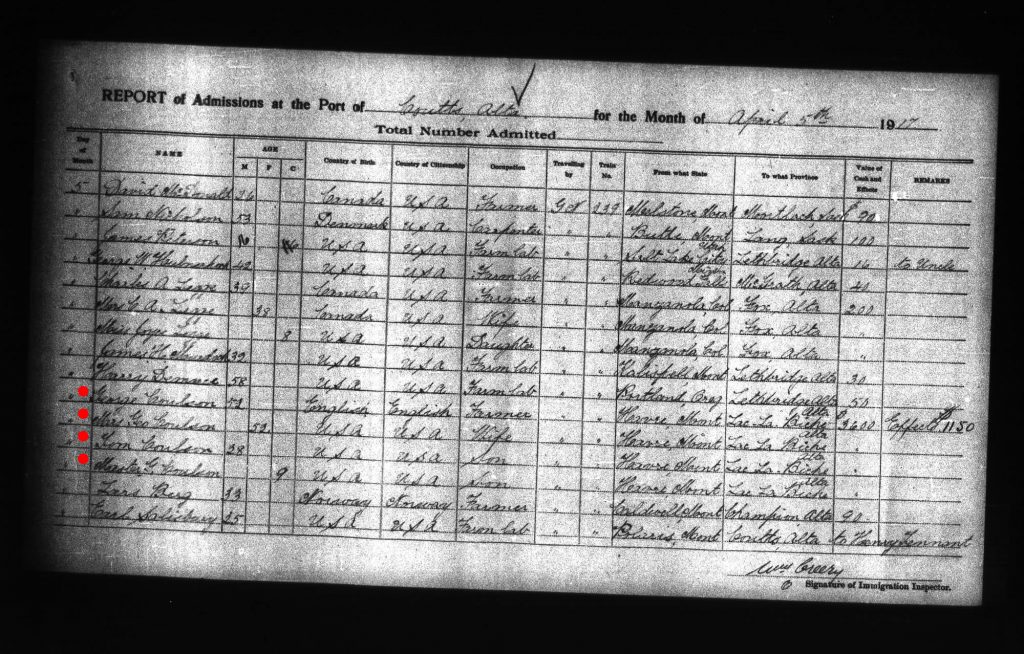

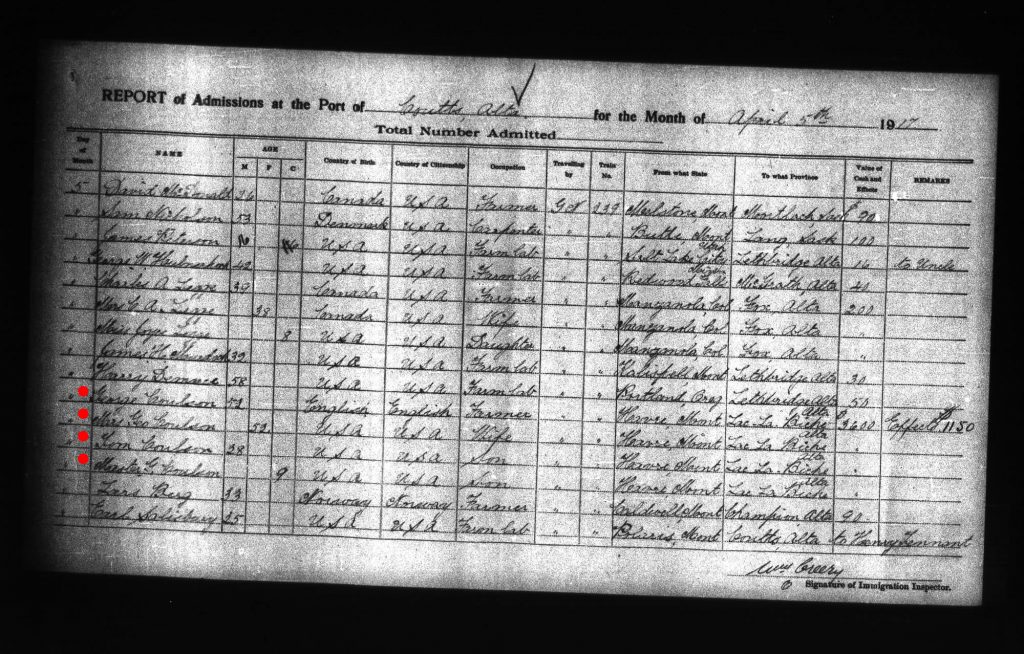

The family kind of fell apart after that, and discovering what happened next has been one of my enduring genealogical quests. My grandfather was only 6 years old at the time of his mother’s death and his recollections don’t really begin until the Influenza Epidemic of 1919. I did find something that gives me a clue, though: a Canadian immigration record from April 5, 1917 at the border crossing at Coutts, Alberta.

That’s definitely my great-grandfather George Lindley Coulson, en route from Havre, Montana, to Lac La Biche, Alberta. Accompanying him are his sons Tom (my Uncle Tom, who later settled in Edmonton and had a big family there) and 9-year-old “Master G.” (that would have to be my grandfather, George Arthur). Also there is “Mrs. Geo. Coulson”.

This is immensely interesting. It seems that after dragging his family to Saskatchewan in 1911, George Lindley eventually drifted back to Havre and got married again. Then he moved to Lac La Biche in 1917. And boy, was he rich! He was carrying $3,600 in cash and $1,150 in “effects”. It looks like he was the richest man on Train #239. Knowing what I know about him I have a feeling he didn’t earn that money himself. I think it must have belonged to this mysterious second wife.

My grandfather never mentioned any of this. I know that George Lindley had a second wife, and all I know about her comes from my grandfather’s recollections of growing up on his father’s farm near Plamondon, a hamlet about 20 miles from Lac La Biche. I know that my grandfather hated his step-mother, and she didn’t like him either; he was chucked off the farm when he was 16 and went to live with his sister in Saskatchewan. He didn’t see his father again for almost 20 years after that, and he certainly never saw his step-mother again; he couldn’t even remember her name.

Lac La Biche, interestingly, has an ancient association with Canada’s fur trade and it played a role in the Northwest Rebellion of 1885. It was a center of Métis culture long before the colonization of the Canadian prairies and it had strong ties to the Red River settlement in Manitoba. This is actually a clue in our story which I’ll return to later.

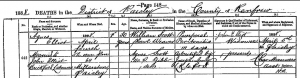

So then I went hunting for the elusive “Mrs. Geo. Coulson” and I soon found her amongst the death registrations in the Alberta Archives. Her name was Mary Theresa and she died on December 23, 1938, in Edmonton. She was born August 19, 1862 in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Her racial origin is listed as French and her nationality Canadian. Religion, Roman Catholic. My great-grandfather signed the certificate, meaning that all this information came from him. She died in the old Misericordia Hospital, which, coincidentally, was the hospital where I would be born many years later.

But here, I at last had a name! Mary Theresa Coulson. Not a maiden name, but it was a start. I used the index of graves at the Alberta Genealogical Society to track her down in St. Joachim’s Catholic Cemetery in downtown Edmonton. I visited the grave site but it’s just a patch of grass. I fear that George Lindley was so poor by 1938 that he didn’t have enough money for a headstone.

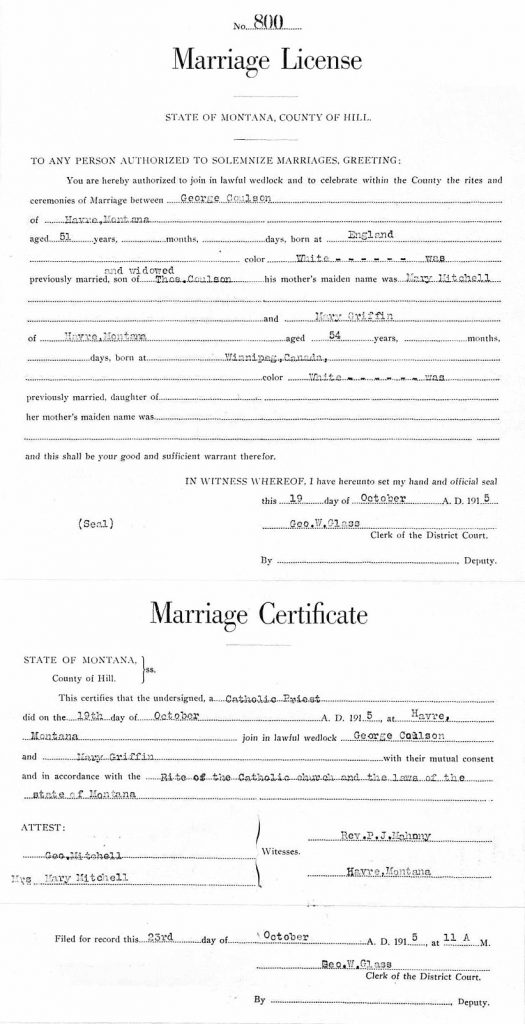

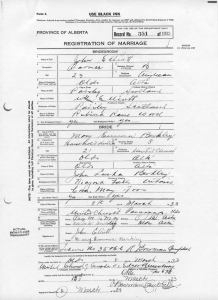

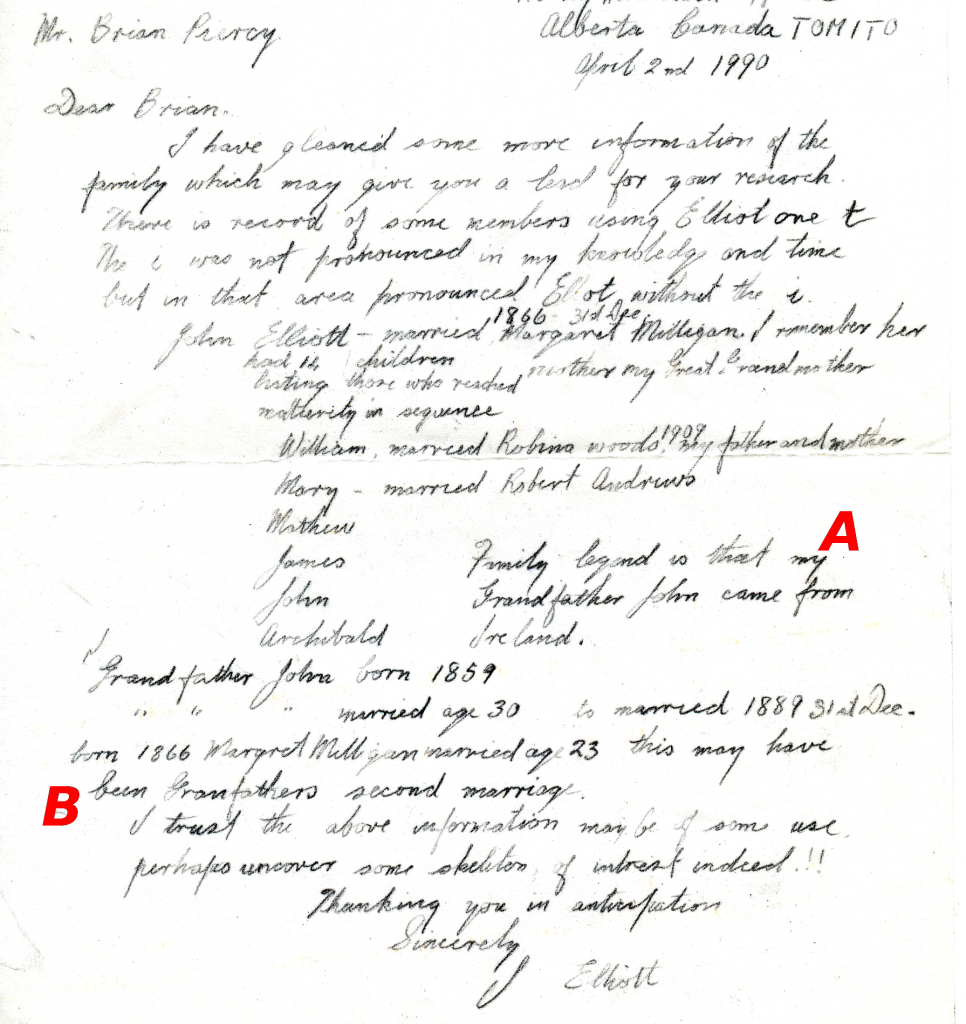

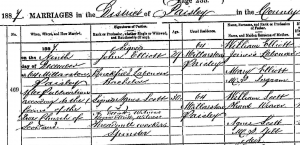

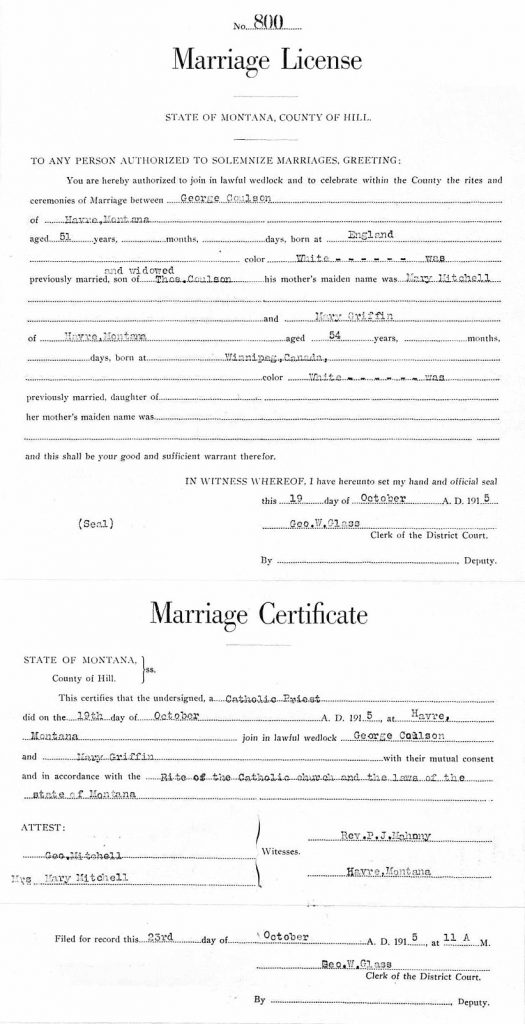

Getting back to the Montana marriage registers, I found the record of George and Mary’s marriage in 1915. Or at least, I think I did. It’s a little confusing.

On October 19, 1915, a George Coulson married a Mary Griffin. Is this the George and Mary I’m looking for? Well, it was a Catholic wedding, which fits our bride. Mary was born in Winnipeg, which also fits. The ages of the bride and groom are a perfect match. But there are two extremely odd things to note: first, the fields for Mary’s parents are blank. Second, the parents listed for George absolutely do not line up with what I know (or think I know). George (according to Aunty Mary’s tales) was the illegitimate son of Mary Coulson and James Barlow, and he only bears the surname Coulson because he was adopted by Mary’s father in order to spare the family disgrace. When this Mary Coulson eventually did get married it was to a man named Henson, not Mitchell. I have got no idea who this “Thos. Coulson” and “Mary Mitchell” are. This might constitute new information for my family tree, or it may be completely spurious.

I questioned the validity of this marriage registration for a long time. Mary Griffin’s marriage to Martin Nelson in May 1914 was another real problem for my timeline, because just 18 months later Mary Griffin married George Coulson. Was this the same Mary Griffin? If Martin had died, I should be able to find a death record for him… Why can’t I? Was this George Coulson my great-grandfather, or some other George? If it’s the same Mary and George, why all the missing and incorrect information on the marriage documents? Did they have something to hide?

And that’s where things sat for quite a while. I was unwilling accept “Griffin” as the surname of my grandfather’s step-mother because this incomplete marriage registration was the sole evidence I had, and it was too shaky. There could have been more than one Mary Griffin in Havre in those days, right? And George Lindley might have gotten married someplace else and I just haven’t found it yet.

That’s when my casual research into Bear Paw Jack Griffin blew the case wide open. Could Jack’s wife Mary T. Griffin, born in Winnipeg in 1862, be the same as Mary Theresa Coulson, also born in Winnipeg in 1862?

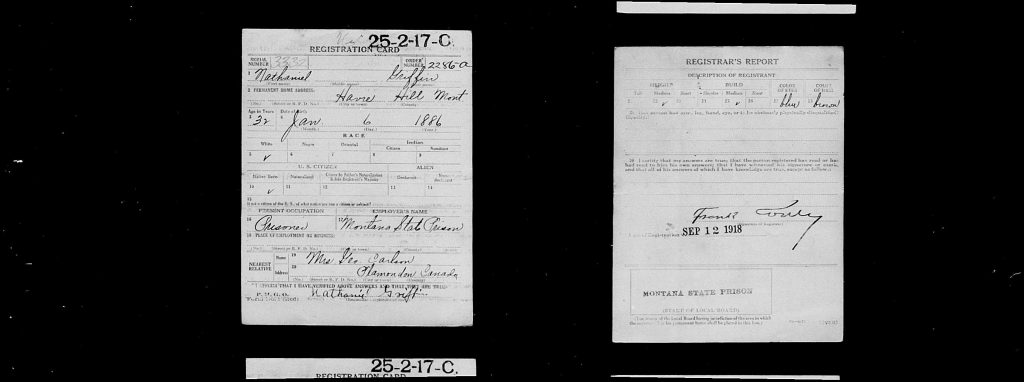

You will remember that Jack’s son Nathaniel had to register for the Draft. His draft card holds the key to this mystery, because on it he identified his mother.

Nat identifies his nearest relative as “Mrs. George Carlson, Plamondon, Canada”. That, without a doubt, is Mary Theresa, whose unmarked grave I found in Edmonton.

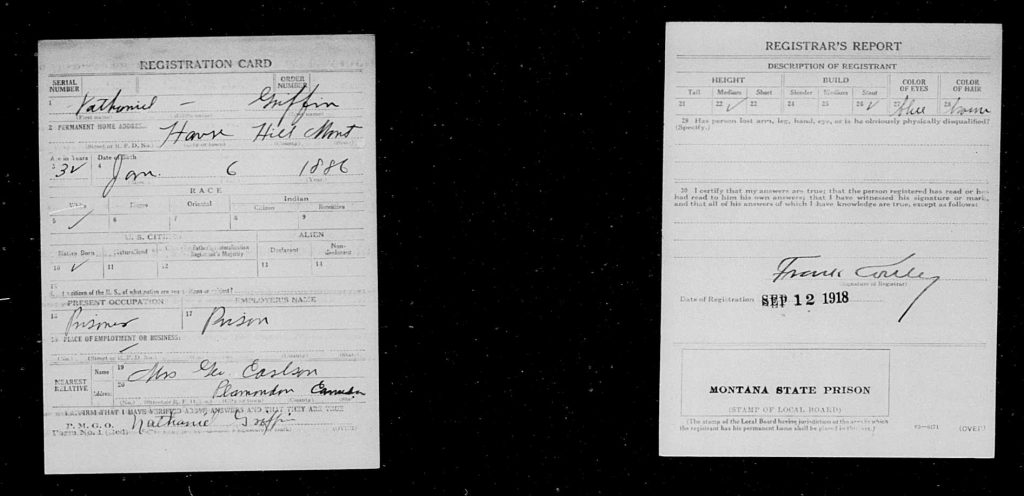

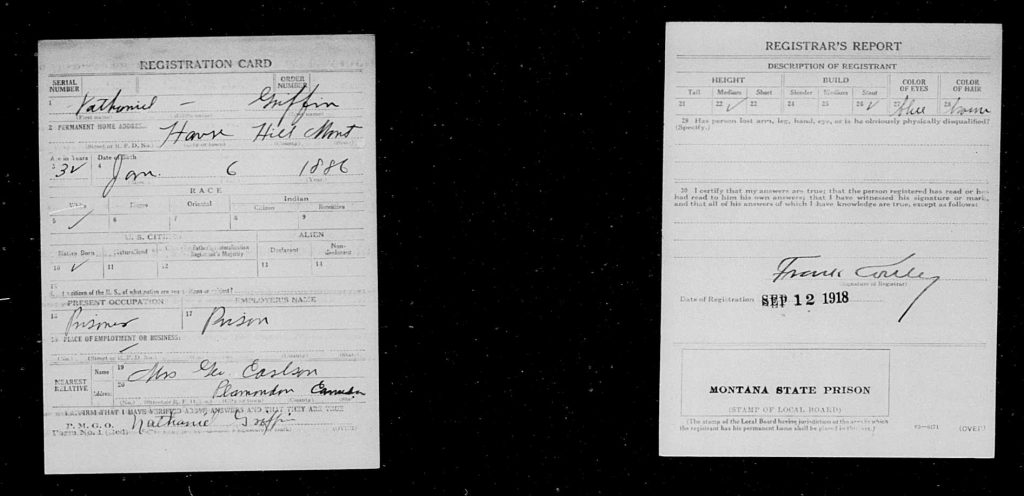

In fact, Nat has two draft cards, both issued on the same day. Here’s the second one:

It’s identical in every respect, except the next-of-kin’s name is changed to “Mrs. George Coulson”. At least it might be Coulson; the third letter in the name is a little squiggly. One can picture Nat trying to remember the name of his mother’s latest husband… was it Carlson? Coulson? How did she spell that? The draft board official did his best to take down both names.

These cards, mentioning the Coulson/Carlson name, combined with the mention of the tiny hamlet of Plamondon, establish beyond a shadow of a doubt that there was only one Mary Griffin, and that she was married both to Bear Paw Jack and later to George Lindley. With this discovery I now feel confident putting the pieces together…

Mary Theresa Paul, daughter of Oliver Paul, was born in the Red River settlement in 1862 when Rupert’s Land was still claimed by the Hudson’s Bay Company, 11 years before the incorporation of Winnipeg. She had a brief marriage that ended around 1879 and she left for (or perhaps fled to) Fort Assinniboine, Montana, which would later become a focal point for the Cree and Métis people fleeing persecution in Canada in the wake of the Northwest Rebellion of 1885. There she met John C. Griffin and became his common-law wife, and together they had a large family and she managed his ranch in the Bear Paw Mountains. They finally got married, and when John C. died in 1913 I would have to guess she inherited his land and was a wealthy woman. She then married Martin Nelson, the Norwegian, and I don’t know what happened to him. Then in quick succession she married my great-grandfather George Lindley Coulson. They decided to move to Plamondon, Alberta, because she would probably have had family connections there via her Métis roots and George was, after all, still a British Subject.

This is probably not the final word on this adventure. I feel encouraged to learn a little more about Métis history than what we were taught in Canadian history class, because now I seem to have a fleeting family connection to it. I’d also like to get confirmation of poor Martin’s fate.

And, I wonder what happened to all that money?

Update: November 7, 2017

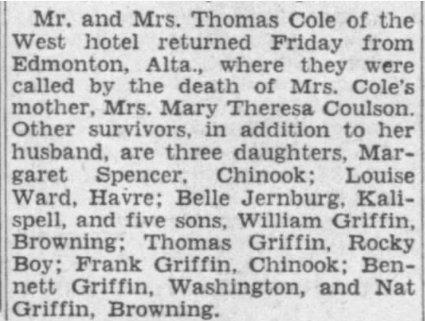

One of the exciting things about airing your family secrets in public is that you never know who you’ll meet. Since posting this story a couple of days ago a fellow-researcher I met on Find-A-Grave was intrigued by the mystery so she picked up the torch and went searching in the Montana newspapers for clues. She came up with a clipping that proves definitively that Bear Paw Jack’s wife Mary T. Griffin was none other than my great-grandfather’s second wife who moved up to Alberta and died in Edmonton. The children’s names– Margaret, Thomas, Frank, Bennett, and Nat– match the ones I already know from the census records.

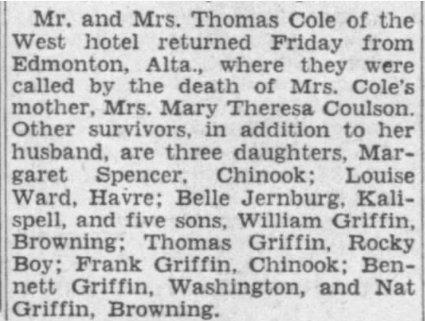

Great Falls Tribune (Great Falls, Montana)

31 Dec 1938, Sat • Page 5

Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Cole of the West hotel returned Friday from Edmonton, Alta., where they were called by the death of Mrs. Cole’s mother, Mrs. Mary Theresa Coulson. Other survivors, in addition to her husband, are three daughters, Margaret Spencer, Chinook; Louise Ward, Havre; Belle Jernberg, Kalispell, and five sons, William Griffin, Browning; Thomas Griffin, Rocky Boy; Frank Griffin, Chinook; Bennett Griffin, Washington, and Nat Griffin, Browning.

Here’s to serendipity and chance meetings on the Internet.